This is an old post and is probably extremely cringe. Please understand that I have moved on from these ideas. Still, it may contain some nuggets that point to some continuity in my thinking over the years, which is why I decided to post it here.

What I’ve Been Working On

I wrote a summary of what I’ve done recently and what I hope to accomplish with this project. I originally intended this to be a preliminary report for Dr. Graham. Take a look:

November Write-Up for Honours Project

Network analysis is used to study the interactions of various entities, whether they are social connections, trade links, political hierarchies, or larger economic models. Rather than examining the attributive properties of each individual component, the relationships between them are the main focus. In the case of this project, I am examining the relationship between various Bronze Age archaeological sites in the Aegean, and the types of pottery that were used by their inhabitants.

In part I am modeling this project off of a similar paper by Tom Brughmans titled “Connecting the Dots: Towards Archaeological Network Analysis” (Brughmans 2010). Brughmans provides a model for making relational and spatial networks, and uses a case study to demonstrate how the distribution and co-presence of artifacts can be mapped on a network. He used data provided by Dr. Jeroen Poblome and Dr. Philip Bes of the Kathelieke Universiteit Leuven as part of the ICRATES platform, and was specifically working with Roman tableware.

The nature of the raw data is crucial to this kind of project. Brughmans used a pre-compiled database of pottery, assembled from dozens of sites around the Mediterranean, with input from the lead excavators. This can be very useful for Roman historians, however there is no such database of pottery available for scholars of the Aegean during the Bronze Age. It is up to individual researchers to assemble a collection of vessels and their properties, which can be a slow and arduous process.

The inconsistency of the data can be problematic, and I certainly ran into this problem while compiling the database of pottery. Researchers at different institutions in various settings may disagree on cataloging techniques, and the excavator’s decisions of what to include or not include when publishing his or her data can effect the theoretical research of scholars who may depend on the raw information. Many of the original excavation reports that I must examine can be up to 150 years old, and the information provided can be either incomplete or not up to date. Scholars that excavated long ago may have excluded some information from publication, assuming that it was irrelevant or unimportant, but did not realize that statistical and analytical methods could be employed to further our knowledge about the history of the site.

At first I started recording the properties of individual vessels that have been found during excavations. The type of vessel, its date, the slip, the fabric, and the decoration were the main attributes that were noted. It was my hope that I would be able to determine the level of luxury based on these three latter properties, however this would require me to take liberties beyond what is academically acceptable. Of course, determining the status of the vessels would only apply to those meant for serving and consumption of food and drinks, or other ceramics that would be displayed in a social setting. There would be little reason to decorate cooking vessels used for food preparation since there is little social significance involved with the “behind the scenes” domestic tasks.

Another major problem with this method that I now recognize is the disproportionate progress of excavations. Even if all of the pottery that has been found was recorded properly and consistently without any of the problems outlined above, excavations may still be ongoing and undisturbed deposits may still lie below the surface. The uneven representation of the archaeological record is something that must be taken into account when running these visualizations, and the prevalence of certain types of vessels should be understood with scrutiny.

With my former goal in mind, I compiled a database of the pottery included in the excavation reports of Palaikastro, Kommos and Kastri, all of which are situated on Crete. Recording the individual vessels for just these three sites took a very long time, mainly because of the problems with data entry that I mentioned above. Looking back, I realize that my biggest mistake was not properly defining what my goals were for this project. Brughmans (2010: 285) put it best:

Research aims will determine for the most part what networks are identified and explored in the data available. Although they are complex on their own, these networks will never cover the full complexity of an archaeological dataset. It therefore becomes crucial to define the nature of the components of a network, their relationships, the network itself, and the meaning of the procedure of every type of analysis from the outset. This is undoubtedly the most important stage in any network analysis, as one could calculate the structure of virtually any kind of relationship between data, but if we do not know what this structure and the resulting patterning represent any results will be meaningless.

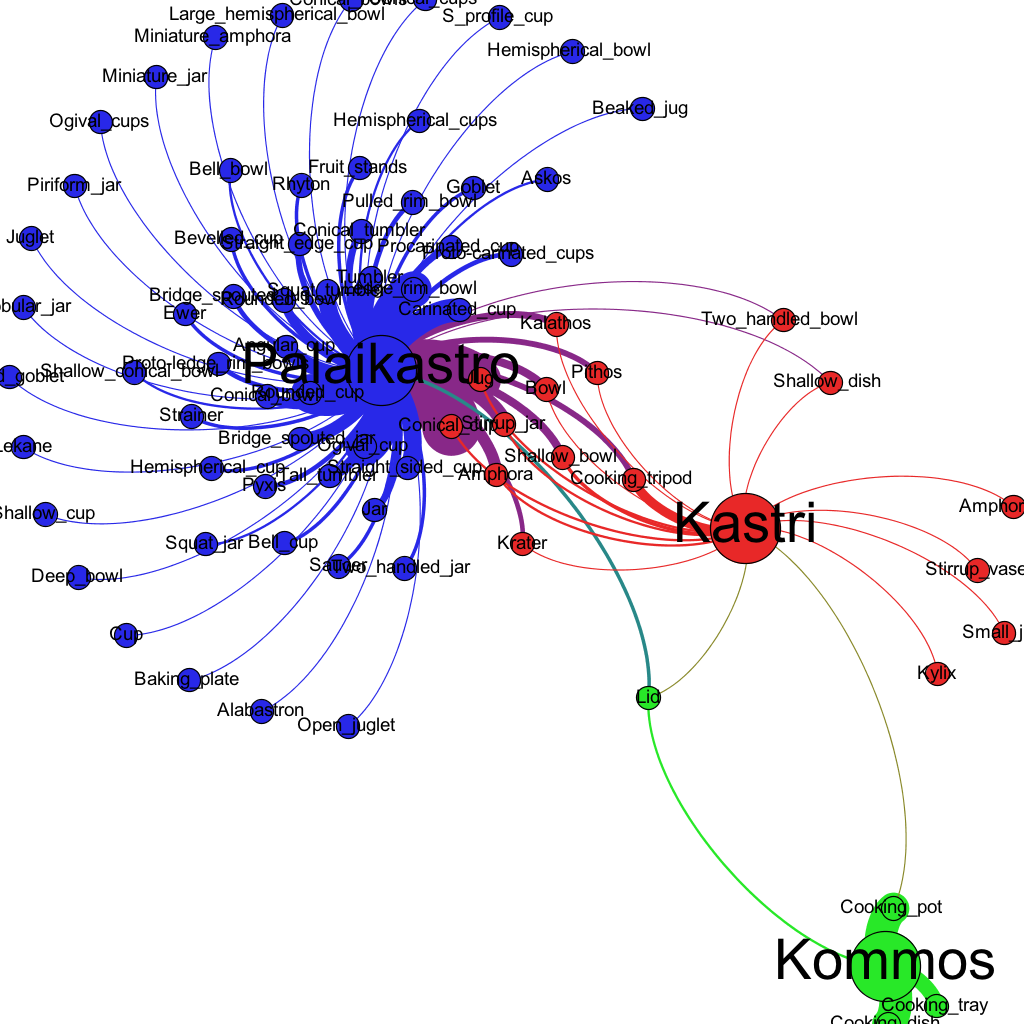

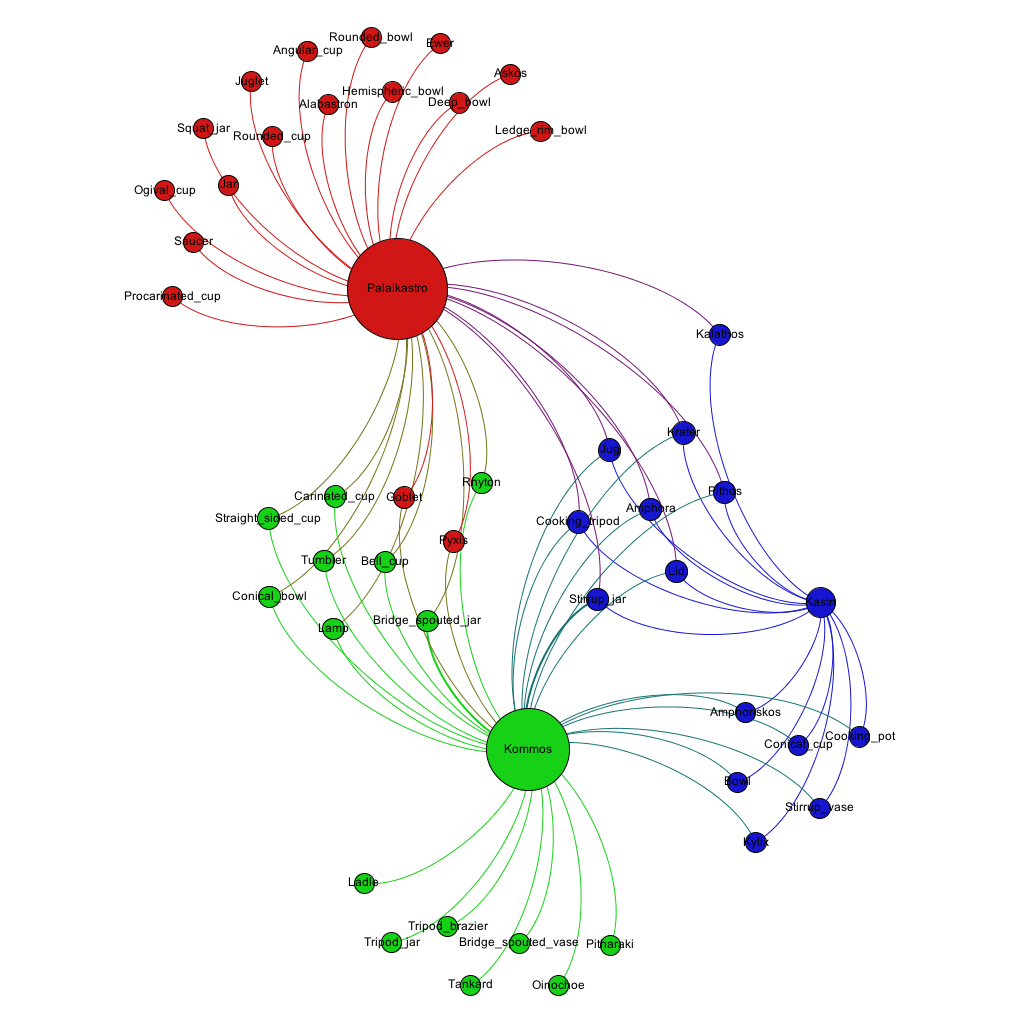

However, just to see what could be produced with the data that I already collected, I ran a visualization of what I had so far ((v4-new?)). Because each relationship between a site and an individual piece of pottery is accounted for, the edges between certain nodes were weighted more than others. My renewed opinion is that it is better to leave out the weights corresponding to prevalence of pottery types. We can still gather valuable results from viewing the distribution of certain vessels without the added weights, while maintaining a proper level of confidence.

In such a way, the visualization can be used to compare the co-presence of pottery types between archaeological sites throughout the Aegean, just as Brughmans did with Roman tableware. It is also possible to look at the adoption of certain types of vessels over time for a particular site. If done properly, links should be made that connect similar pottery types with periods immediately before and after each other. This can help us create dendograms depicting the typologies of ceramic vessels for a particular site. Then the dendograms can be compared with those of neighboring towns, and patterns of regionalism can be noted. This can even fit in with a larger network of the Aegean, with each region’s variation acting as a different module in a larger context. I think that this is an exciting prospect, and I am excited that this can fit into a broader context.

Additionally, it is possible to measure the betweeness centrality within a module representing a particular region, and if types with high values are also present outside of this specified area, we can determine the amount of contact that the region had with the rest of the Aegean. Perhaps this can be traced as a layer to the spatial network created by Carl Knappet, Tim Evans and Ray Rivers that mapped sailing routes in the Aegean (Knappett, Evans, and Rivers 2008). It would be very interesting to see whether or not the two networks compliment each other.

Now that I have demonstrated what can be done in the near future, I’ll explain the results that have already been attained ((v5-new1?)). This network does not focus on a specific time period, but rather examines the site as a whole. Once more data is collected for various sites it will be possible to visualize shorter intervals. As expected, the modularity for this network suggests that there are three main groupings of pottery, each arranged around a particular archaeological site. However, at Kastri there seems to be no types of pottery that occur solely at that site. This is probably because of the incompleteness of the data and the unavailability of certain excavation reports. Once all of the data is available I’m sure the network will look quite different.

The betweeness centrality and other properties regarding path length do not seem to have any significance at this point, probably due to the rudimentary data. Since there are only three sites in the network, the maximum impact that a single node can have on the entire network is dependent on how many edges it has. Right now, the network is very simple, but as more data gets collected and input I imagine it will get much more complex and some interesting patterns might emerge. As I mentioned above, measuring the betweeness centrality can be very useful later on when examining the interaction between modules in a larger Aegean-wide context.

Clearly, the next steps for me to take should be to record more data so that it can be added to the network. Without working on this first step I cannot advance to the next. In order for me to do this I need to acquire these reports from the archaeological sites, which has been very troublesome so far. Many of these reports are not available at any libraries accessible to me, so I must loan them from universities in other cities.

I am very eager to begin the interpretive phase of this project and start analyzing the results. There are many interesting things that can be done using network analysis, and I am seeing a lot of value in these methods. Hopefully all of these things outlined here can be incorporated into my honours project. Even if time acts as a constraint, perhaps I will complete these goals later on in my academic career.

Comments:

Mattea: Hi Zack, I’m a student at Carleton too, and found out about your project on wine in the Aegean through Doctor Graham’s blog. I really love my ancient history, micro-history, and gastronomical history so I’m going to come back and look at this from time to time. What I’ve read so far looks super amazing: I love that you tried to recreate the wine. I loved Horrible Histories as a kid by Terry Deary, and he has a wine recipe in his Rotten Romans book. Anywho, I also wanted to briefly comment that you mention the “Kathelieke Universiteit Leuven” in your report, and forgive me for mentioning this, but I just wanted to let you know the correct spelling is Katholieke Universiteit Leuven. I just mention this because I’m Belgian and know the spelling. I hope that’s okay. Keep up the great work!

Zack: Hi Mattea. Thanks for your interest! Although this blog was made to to document my honours project, which Dr. Graham is supervising, it has gone a bit off track and less specific. However, I plan to write more frequently, so having people actually read it is a great motivator. Maybe we’ll even see each other on campus this semester. And thanks for the comment on the spelling, I’ll make the proper changes.