Scholarly metadata pertaining to monographs and grey literature

Since the spring, I’ve been working with Julie Lund and Isak Roalkvam on a project to analyze the development of ideas concerning the origins of the Viking Age through a bibliometric analysis of a large corpus of published work. The project itself is very interesting, and I will post more about it when we get some significant findings, but now I just want to share some frustrations and challenges we’ve been experiencing, which may represent a bigger problem with representativeness of scholarly pluralism in open science.

Basically, we want to explore the web of citations being made in hundreds of scientific works, and in order to do this we need to obtain information about each work and about the works that they are citing. We will then analyze the network analysis of bibliographic citations, while also incorporating some additional information such as affiliations as well as qualitative evaluation of topics covered by each paper.

However, we’re facing significant problems obtaining reliable scholarly metadata about monographs, chapters of edited volumes, and grey literature — which makes up a significant portion of archaeological literature. So in this post I outline the series of decisions we made and the roadblocks we experienced. We still haven’t quite arrived at a solution, so in a way what you’re about to read is an articulation of a work in progress, but one which reveals some inadequacies with the open infrastructures that we have built and a testament to the overconfidence we ascribe to them.

Tapping scholarly metadata resources

The most common approach in bibliometric studies, or in meta-research that rely in whole or in part on scholarly metadata, is to access Crossref. Crossref is an open resource that registers information from virtually all modern academic publishers. It is one of a few such registries, existing alongside Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar. What makes Crossref distinct is that it’s a registry rather than an original source of data — publishers enter required and optional metadata into Crossref, and Crossref draws associated records together using a unique digital object identifier. A similar process applies for DataCite, which specializes in data resources, as opposed to published journal articles, and PubMed, which specializes on topics relating to medicine. Several additional services like OpenAlex, Lens and Semantic Scholar run on top of Crossref and other related data sources, but they are fundamentally based on the same data submitted by publishers. This is why your Zotero library is so messy.

Problems of scope

Crossref is the most open scholarly metadata resource, but it’s also quite limited in its scope: it’s primarily comprised of journal articles, and has very limited coverage of monographs, book chapters, pre-prints, and experimental genres and styles. Using Crossref as data source for meta-research is therefore much more appropriate for analysis based in science, technology, engineering and medicine (STEM), since these fields rely fairly uniformly on journal publishing. On the other hand, the social sciences and humanities (SSH) regularly publish their work as whole monographs or as chapters within edited volumes, publish in smaller journals or government-hosted “grey literature” venues not registered by Crossref, and participate in experimental publishing practices. In other words, the range of scholarly works is much broader in SSH than the scopes that delimit Crossref and other scholarly metadata registries.

Since the corpus we want to compile includes monographs, chapters in edited volumes and grey literature, we are unable to rely on Crossref and other scholarly metadata resources alone. Moreover, after briefly investigating the field of scholarly metadata, I was left extremely disappointed by the prospect that we would ever be able to obtain reliable metadata at scale pertaining to these missing kinds of resources. It’s especially difficult to obtain the lists of references cited in each of these resources..

While Google Scholar has by far the best range of resources, it has a few significant drawbacks:

- There is no API. It can be scraped using some workarounds (see the documentation provided by Publish of Perish), but this is not ideal.

- It does not provide unique identifiers such as DOI, and these need to be added through reference to the Crossref API, which re-introduces the problem of scope.

- It does not include lists of references cited, which is a core set of information we need.

With regards to Scopus and Web of Science, based on my own brief experiences, they do include a significant amount of data on monographs and book chapters, but the quality seems very inconsistent. Quality is especially quite low for monographs not written in English, which is the case for much of the literature included in our analysis of largely Scandinavian-led archaeology.

Open Citations

A key aspect of our study is analysis of citations, and it’s fantastic that the Open Citations database exists to support this kind of work. However, initial testing showed significant discrepancies between the numbers of citations in Open Citations, Crossref and Google Scholar. So for the sake of consistency, we decided it would be best to rely on one source of information; i.e., if we are using Crossref, use the information provided by Crossref in all respects.

Moreover, although I haven’t tested it explicitly, it seems that Open Citations primarily indexes recent journal articles, similarly to Crossref. This may significantly impact the accuracy of its data, especially in fields that rely on monographs and grey literature.

Web of Science also includes a significant amount of data about bibliographic references made by various works, but like with other aspects of its database, the scope of this facet, especially when it comes to books, is inconsistent.

I was also referred to look at OpenAlex to investigate webs of references. However, it is now well documented that this aspect of the Open Alex database is extremely deficient and unreliable (see Alperin et al. 2024; Culbert et al. 2025).

Extracting metadata from PDFs

To work around these issues, we tried circumventing scholarly metadata resources and looking directly into the texts themselves, especially monographs and grey literature whose coverage is most significantly lacking. Specifically, we experimented with Grobid, a machine learning system designed to extract scholarly metadata about individual files and about the references they cite.

Grobid is actually quite good at reading PDFs of journal articles, but generally fails to produce reliable data for monographs and grey literature. This is because of the training data that informs the machine learning algorithm: it is only designed to work with journal articles. It’s also not trained on what the maintainer refers to as “humanities style references”, which may refer to references to books, but may also include footnote-style references or references that include ibid, id or other Latin abbreviations beyond et al. Moreover, it is primarily trained on a corpus of works written in the English language. This is evident through discussion in this GitHub issue posted by a team looking to extract information from dissertations: https://github.com/kermitt2/grobid/issues/809. Of course, this is a matter of training the model to pick up on these things, but generally speaking there is so much diversity in SSH works and citation styles that I will always be less confident in the results.

One significant aspect of the Grobid tool is the ability to “consolidate” the reference, which effectively normalizes the extracted records against the Crossref database, or against a combination of the Crossref, PubMed and ISTEX databases. However this simply re-introduces the same biases as mentioned above. I did create a GitHub Issue to inquire about the feasibility of consolidating against Google Scholar, and I regret that I haven’t had much time to reach out for more in depth support, which the maintainers have kindly offered.

Moving forward

So right now we’re at a point where we need to reckon with what we really need to get the job done. Realistically, to construct networks, we only really need unique identifiers for each record, not the full record. So that might simplify our processes. We may also simply sample the dataset based on preliminary exploratory findings.

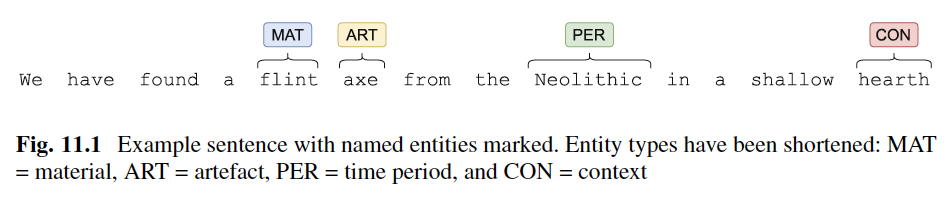

Ideally, we would be able to do something like what Alex Brandsen (2023) accomplished: extracting specific kinds of information from archaeological publications using machine learning techniques. But neither of us really has that kind of practical expertise, at least not yet, anyway.

Overall, the situation is kind of challenging, but potentially very rewarding too. Grappling with these issues makes the difference between a rather uniformly lazy meta-science approach and good social scientific research. It is not acceptable for us to simply pick up the data that’s already available, since unfortunately this includes significant biases that would severely hinder our findings. So we need to actively make the data work for us so that they address our research questions, rather than do things the other way around.